The valley of solitude of technical illustration

I recently shared a post on a Facebook group of illustrators and designers with more than 100,000 members asking if anyone there worked or was interested in technical illustration. The responses were overwhelming: 2.

It doesn’t surprise me. Finding people who are passionate about technical illustration in the social networks where I share my work is always challenging. It doesn’t matter if we talk about dribbble, ArtStation, Behance, Instagram, AOI or any other; it seems that only a few of us dedicate professionally to this art.

And who the [bleep] is going to like taking technical drawing lessons?

I get it. I myself hated technical drawing classes in school, even though drawing has been a passion of mine for as long as I can remember. I recall the frustration of feeling held back by a series of geometric rules that restricted the freedom with which I drew outside of that class. If someone had told me that as an adult I would end up doing technical illustration for a living, I would have never believed it.

Why is technical illustration the “ugly duckling”?

I think that one of the reasons why technical illustration is the “ugly duckling” of art and does not have many followers is precisely that clash between the rules of technique and the freedom of drawing, a clash that is particularly evident in the first approaches to technical illustration, which make it seem more difficult than it actually is.

Another reason may be the fact that the romanticized concept of creativity is usually associated with all the illustration techniques – except, of course, for technical illustration. I must admit that I also saw it that way once; however, limiting the scope of creativity and making it exclusive of certain areas is depriving oneself of endless possibilities.

Finally, the process one needs to follow in order to achieve a good quality technical illustration can be intimidating for those who are reluctant to go through the field of mathematics and geometry; which, in addition, are only the beginning, because depending on what you want to illustrate, you also need to understand concepts of engineering, mechanics, technology, science, information flow and more.

Never say never

Over time, I ended up accepting that all my childhood I had been a “closeted” technical illustrator. By means of trial and error, in a self-taught manner, I realized that the rules that I once saw as limitations or obstacles to drawing were actually the foundations that helped bring the images in my head to life, exactly as I had envisioned them. These rules ended up becoming the three-dimensional grid through which I was able to trace freely, without compromising my obsession. The more rules I learned – I came to understand – the more tools I had to work with even more freedom.

A structure to dream

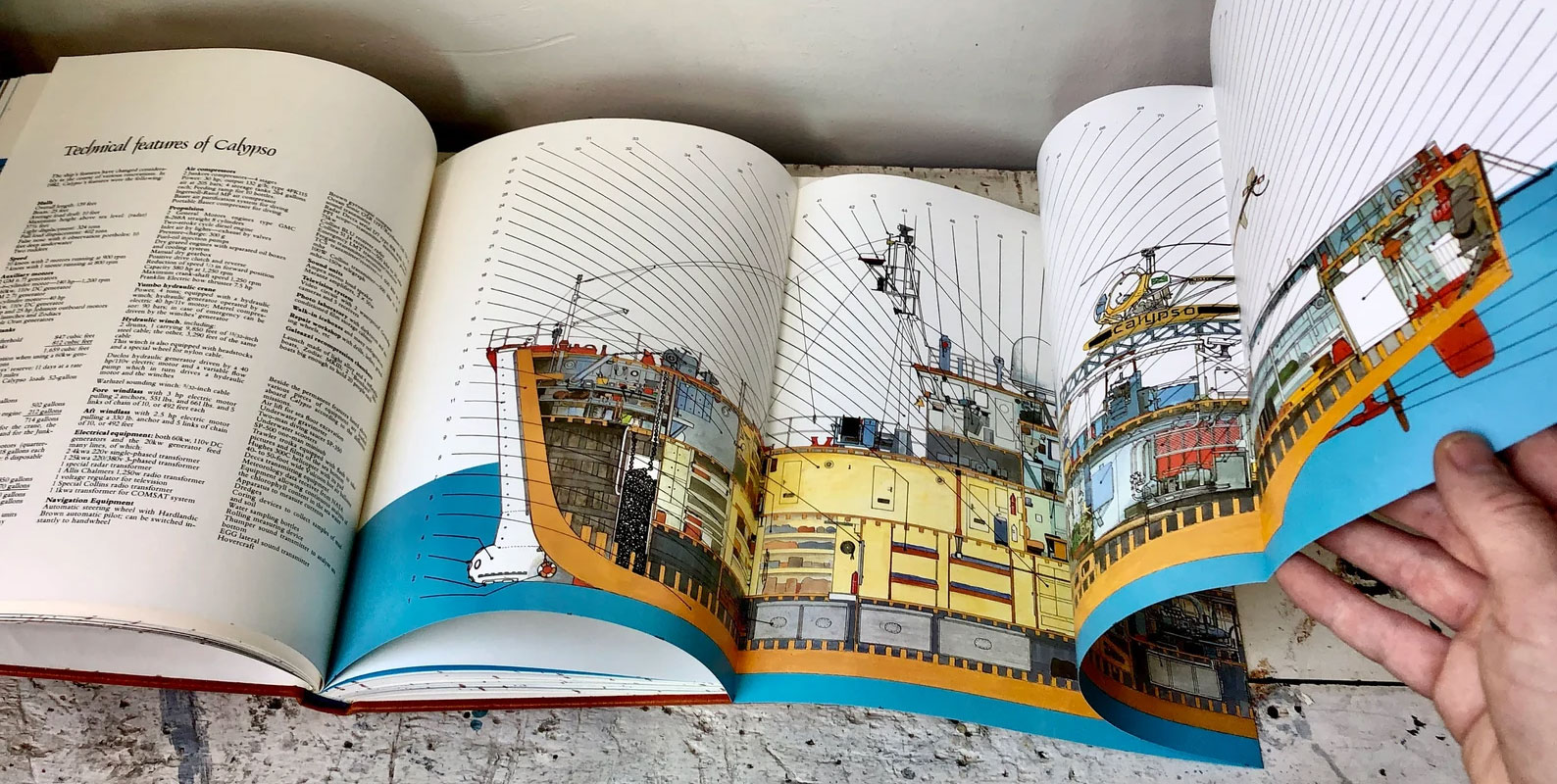

One of the first works of technical illustration that caught my eye was the one that Alexis Sivirine did for Jacques Cousteau’s book Calypso from 1983 (I was 6 at the time). I could spend hours poring over every detail of the interior of the famous ship in an impressive color foldout, its plans, or the evolution it underwent from a minesweeper to a fully equipped oceanographic vessel. I dreamed of traveling aboard the Calypso and even building my own boat. Thus, I started to draw ships sailing in waters teeming with marine life.

Foldout with illustration by Alexis Sivirine for the book Calypso by Jacques Cousteau.

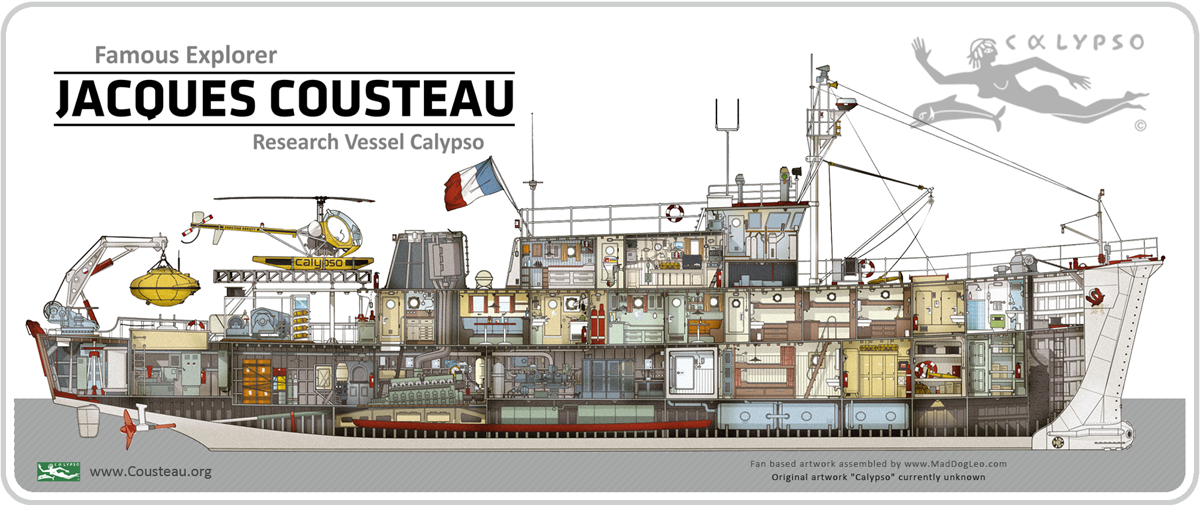

Illustration by MadDogLeo.com inspired by Alexis Sivirine’s work.

Geometric evolution

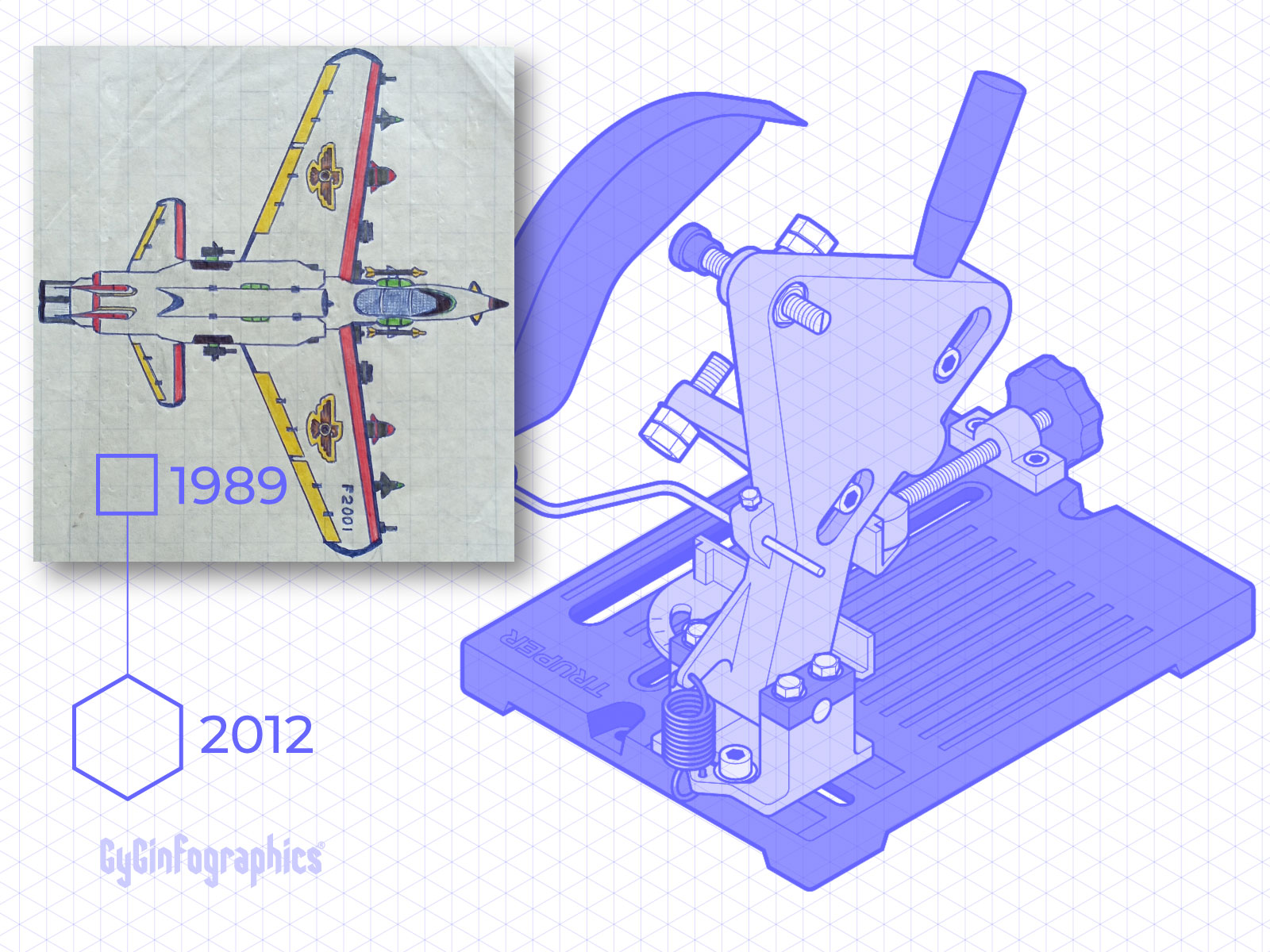

Then the airplanes came, and I discovered how useful the blue grid of school notebooks is to draw them. I didn’t stop; I continued to explore on my own, first paying no attention to mathematics and geometry, and later coming to terms with them and using them in all my illustrations.

To this day, I continue to explore and find new forms of applying mathematics to find different paths for my strokes. For years, my style has been characterized by the use of isometric projections with lines at certain angles to achieve three-dimensional effects. This may sound overwhelming, but once you get used to it and manage to systematize all the angles and arithmetic calculations you need to draw, you get very satisfying results, which you can easily reuse over and over again.

Regarding creativity in technical illustration

In short: yes, you do require a lot of creativity to find the infinite paths that geometry hides to guide the strokes of a good technical illustration.

The unsuspected advantages of technical illustration

• There is little competition

On the other hand, being part of such a small community within the world of illustration is not that bad; that way, there is enough room for everyone to find our niche comfortably without the fierce competition that other illustrators face.

• The client’s adjustments are usually reasonable

Another advantage that I love is that our work is not susceptible to the whims that clients usually indulge in when they commission art to illustrate highly subjective subjects. In the world of technical illustrators, there is no such thing as “Add more design elements!” or “Can you tweak it a little more?” We usually work for clients who know exactly what they want (engineers and developers mostly), and we know how to do our job well to solve their communication problems. If I am commissioned to illustrate a submarine for a technology magazine, I can be sure that at no time will I be asked to add more hatches because the editor suddenly felt like it.

• Detection of problems in blind spots

One more benefit of technical illustration is the scanning and detection of mistakes. I have to be extremely meticulous when interpreting the material that my clients provide as reference for the illustration. By studying this material, and during the drawing of the illustration, inconsistencies in the products can be detected – and therefore, corrected – before the publication of their technical documentation. I talk about this in the post Truper Manuals I.

• Work valued

And of course, there is the possibility of a worthy retribution. Specializing to be able to grasp the intricate thought process of those who work in science, engineering and technology and translate it into an illustration that everyone can understand, is highly valued by the clients who develop projects in these fields.

My heroes of technical illustration

Finally, I would love to share the work of some incredibly talented technical illustration artists who inspire me and still make me feel the same way I felt when I used to become lost among the lines of Alexis Sivirine’s illustrations as a child:

Tony Matthews

Tony is a true inspiration as a technical illustrator in the automotive industry. He transmits his passion for motorsports through the lines he uses to give life to the intricate components and mechanisms of the Formula 1 engines that have been part of his work for decades.

Superpowers:

- Applying ink

- Watercolors, gouache and airbrush

- Knowledge of engineering

Rafael Araujo

Rafael’s talent for drawing and making mathematics visible is second to none. His studies of the golden ratio or the flight of butterflies reveal the mathematics that are usually hidden in plain sight, but which give meaning to the universe around us.

Superpowers:

-

Mathematical stroke

-

Knowledge of the golden ratio

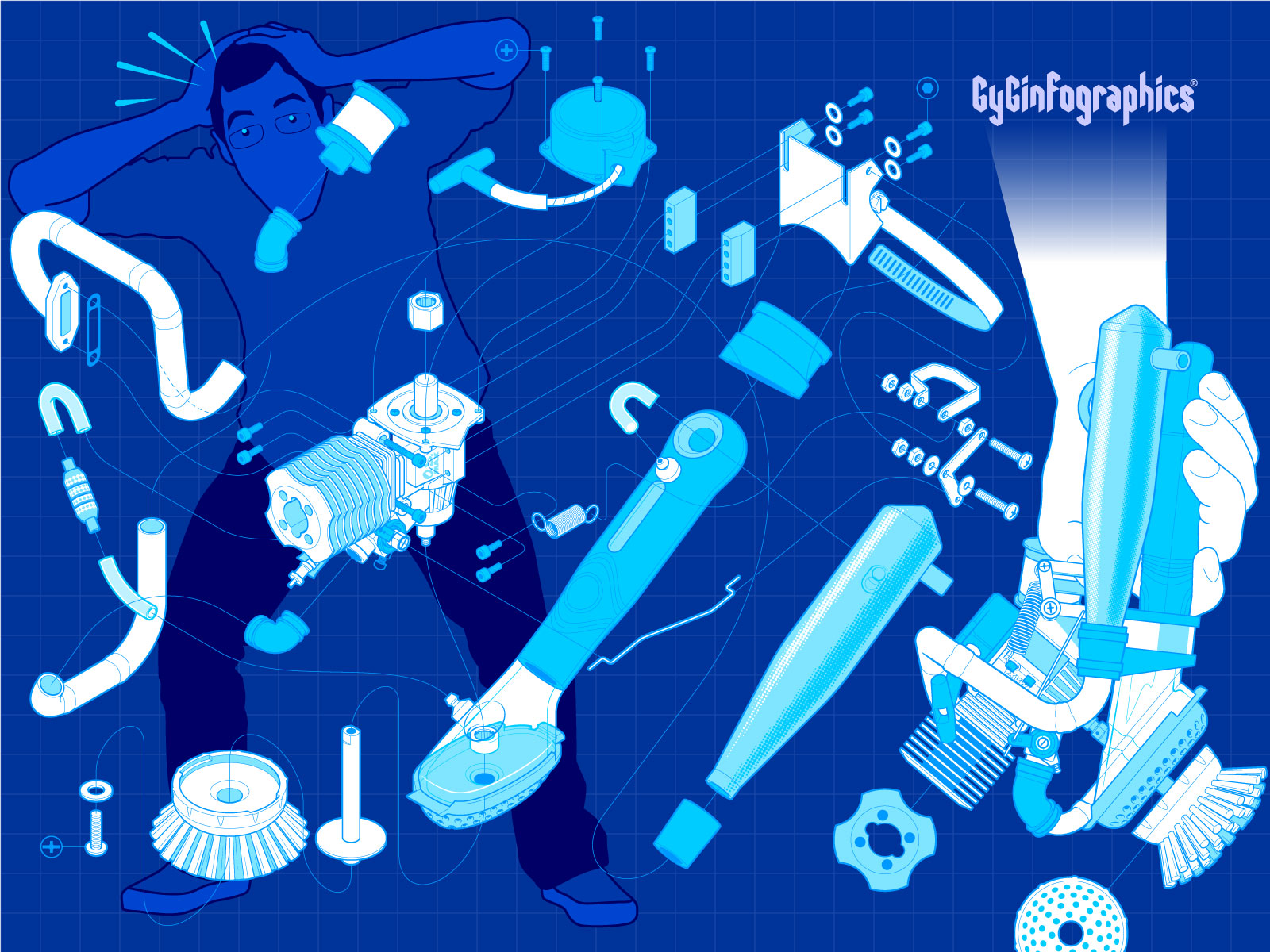

Max Degtyarev

In addition to making amazing illustrations to describe the operation of various devices, Max is an expert in capturing pop culture scenes that are filled with endless details. One can spend hours poring over them, discovering hidden stories within stories.

Superpowers:

-

Combining traditional and digital techniques

-

Use of color

I hope that this article has served, in some way, to exalt the art of technical illustration, and to encourage those who are considering approaching this fantastic world; come on in, make yourself comfortable. We have plenty of room.

Do you know any other technical illustration artists?

Thanks for reading and sharing.

Francisco GyG

Translation: Aron Covaliu.

0 comentarios